Chamber Chekhov

Charles Spencer, Evening Standard, November 16 1979

"Isn't this a ghastly place,"said Nigel Hawthorne, as he led the way into the cheerless church hall where the rehearsals are now in full swing for the Hampstead Theatre's revival of Uncle Vanya.

Inside yes, but outside was a day Chekhov himself would surely have relished. Huge blue skies stretching for miles over London, the stench of dying leaves, watering sunlight filtering in through dirty glass doors - a last bright burst before winter gloom, as bittersweet as Chekhov's own remarkable plays.

There's a formidable cast, Jean Anderson, Susan Littler and Alison Steadman head the ladies and the male leads are being taken by two of Britain's most consistently reliable and versatile actors - Hawthorne as Vanya, and Ian Holm, last seen disintegrating horribly in Alien, as the doctor, Astrov.

It's Holm's first stage appearence since The Iceman Cometh three years ago and it's no coincidence that he's chosen to return to live theatre with Hawthorne.

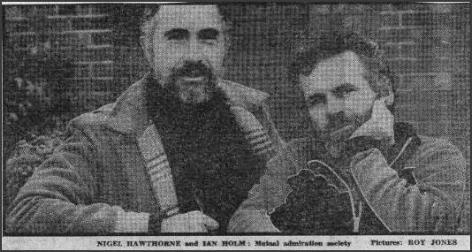

"I accepted this for one reason and one reason only that's because Nigel Hawthorne's in it. We are a mutual admiration society." The two recently worked together on a television version of The Misanthrope.

As befits a mutual admiration society, the two look remarkably alike. Both are fityish, sport greying, grizzled beards and approach their craft with a seriousness which never becomes stuffy or pretentious. The prospect of playing Uncle Vanya in a small, intimate setting, a chamber Chekhov, clearly excites them.

Both actors identify strongly with the characters they are playing. Said Hawthorne: "Vanya is obsessed with the fact that he's wasted his life. He's put all his energies and talents into supporting this professor whom he suddenly finds to be bogus and without any talent.

"As an actor I did not get going at all until I was 40, which is a lot younger than Vanya, but even at 40 when nothing was happening to me in the profession I had chosen I had a tremendous feeling that I had wasted my time."

Both men also see life with Chekhov's own, distinctively tragi-comic squint. "You get to a certain age and you've lived a bit of life and you realise that the things people do terribly seriously can never really be seen as totally serious.

"There's always an absurdity and that's the joy of working with Chekhov because he saw it," said Hawthorne. Holm agrees, "There's an air of cynicism creeps in the longer you live on this planet. You lose your innocence which is sad."