Play that makes no concessions

The Fire that Consumes (Mermaid)Irving Wardle, TheTimes, October 14, 1977

If Henry de Montherlant had fears of exposing this work to the moral climate of France in the 1950s, what would he have felt about its English-language premiere in the godless and licentious seventies?

The story of a Roman Catholic teacher in love with one of the boys, who pursues his obsession to the point of getting his rival expelled, the play covers similar territory to Mary O'Malley's Once a Catholic. But, of course, Christianity still holds sway in Montherlant's world and his view of M L'Abb� de Pradts's spiritual torment is liable to collide with the popular view of the abb� as a dirty old hypocrite.

The play makes no concessions at all to our reductive attitudes: nothing about the frustrations of institutional life, nothing about physical homosexuality. It gets as far as a kiss and a blood pact between the two boys, but otherwise Montherlant veils such relationships as "sentimental friendships".

I cannot pretend to warm to the play, but the least one can claim is that it contains as much truth as Miss O'Malley's rollicking satire. There is more to adolescent affection than the genitals: and more to the teacher's desires than sexual repression. And Montherlant's treatment of the monastic triangle succeeds in doing sympathetic justice to each character within a deftly articulated plot.

There is, however, another barrier as formidable as that of sexual fashion. When the Th��tre Michel brought the play over as part of the 1971 World Theatre Season it was accepted as an accredited French cultural export. In Vivian Cox's very speakable translation one is brought up hard against that alien tradition.

For Montherlant's audiences, fed on the French classical repertory, the play might appear a legitimate descendant of the drama of noble renunciation along the lines of Racine's Berenice (the expelled schoolboy is rehearsing a Racine tragedy). But for us, the solemnity of the style, the intensities of emotional analysis, the prolonged, formal speeches (culminating in a tremendous ticking-off from David William's Grand Inquisitorial Father Superior) seem wholly out of proportion to a play about schoolboys getting up to no good in the games pavilion.

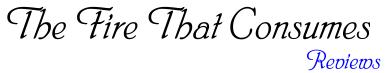

I would, however, recommend Bernard Miles's production as a work of manifest integrity, with a superb central performance by Nigel Hawthorne as the Abb� (witness the impulsive slips of his authoritarian mask) and a matching display of volatile danger from Del Bradley as the boy friend. The confinement of the action is well embodied in Adrian Vaux's angled platform, a much lived-in space isolated in the centre of a bare stage.

David William, Nigel Hawthorne: Mermaid

David William, Nigel Hawthorne: Mermaid

MERMAID

Michael Billington, Guardian, October 14, 1977

Fire That Consumes

HENRY de Montherlant's The Fire That Consumes (originally La Ville dont le Prince est un enfant) is a very fine play indeed and I am glad that the Mermaid has had the courage to stage it. But, compared to the Racine-like severity of Jean Meyer's production. which played at the World Theatre Season six years ago, Bernard Miles's is unduly coarse and corporeal. It is, in fact; about as French as boiled beef and carrots.

Set in a Catholic boys' college in Auteuil, the play deals with a priest's possessive passion for a fourteen-year-old pupil which leads him to victimise the child's schoolboy lover. And the whole point of the play lies in the contrast between the classical severity of the form and the high emotional content. Scene after scene takes the shape of a tightly-controlled duologue in which the participants adopt the roles of priest and confessor. And the final Act offers a marvellous confrontation between the Father Superior and the errant priest in which two kinds of love are violently opposed: sacramental love which is a negation of self and secular love which is based on tenderness, impulse and instinct.

At this point the Mermaid production takes off. But before that it resembles nothing so much as a louche version of Tom Brown's Schooldays. Take the scene in the Games Pavilion where the two schoolboys swear eternal friendship and become blood-brothers. The whole point is that their meeting is physically innocent and that the older boy is unfairly expelled when they are caught together. Yet here they indulge in a long, passionate kiss which makes them look like liars and gives the priest a moral justification for his action. Meyer's production was based on stillness and strenuous, hard-won discipline: Miles's is restless, literal and less about a "tempest of the spirit" than a storm in a teacup.

Only at the end does it begin to jell. Nigel Hawthorne's Abbe, who earlier misses entirely the priest's poker-backed cruelty, becomes very moving in his breakdown into an unmanned hysteria, his nails biting into the palms of his hands in desperation. And David William as the Father Superior makes his confession of youthful passion all the more powerful for the iron self-control with which he delivers it. I applaud the Mermaid for doing the play, smoothy translated by Vivian Cox. I only wish the human vulnerability it describes were placed against a believable background of catholic rigour and repression.

The Fire that Consumes

Sunday Times, October 23, 1977If I tell you that The Fire that Consumes (Mermaid) consists of a debate on the nature of sacred and profane love, you may well run for the hills, leaving no forwarding address. I must therefore tell you also that de Montherlant's play makes one of the most dramatic and absorbing evenings the London theatre at present has to offer, that it is exceptionally well acted, and that anyone who can appreciate a civilised, eloquent and discreet presentation of enormous themes will be making a profound mistake in failing to see it.

Set in a Catholic boys' school, it depicts a relationship which in hands of lesser skill or integrity could be either disastrously coarse or fatally sentimental : a priest sets out to break up the pure but potentially dangerous passion of an older boy for a younger, driven by his own uncontrollable love for the child. (I had better add here that none of the three so much as touches either of the others.)

The irresistible force meets the immovable object in the compassionate cruelty of the Father Superior: it is not made clear, and I think is not meant to be, whether his arraignment of the errant priest-teacher is inspired by his expressed belief that human love can take true root only in the love of God, or whether he has killed the capacity for love in himself after the similar experience he recounts from his own youth.

That is all; but it is much. There is wonderful tenderness in the older boy's honesty, self-sacrifice and devotion, real agony in the priest's crushing and suffocating guilt; there is wisdom and understanding in the immense duel at the end between the priest and the Father Superior, when the man who has sinned venially in his heart comes close to mortally cursing the God who taught man that the most important thing in life is love, but failed to define it; there are some penetrating statements of truth, such as "If you are telling me all that to put my mind at rest, I should tell you that men of my calling were not intended to have our minds at rest"; there is fascination in the way the author leads us to see that although there is sin on his stage, there is no evil, and that salvation is possible for all three souls in the triangle. And there is an additional pleasure for anyone as sick as I am of playwrights who cannot stop effing and blinding and waving their genitals about, in the sight of a masterly writer who can plunge into the heart of "the fire that consumes but gives no light" without a single swearword or ambiguous gesture. Do I really need to add that he thus achieves ten times the effect of the effers and gropers?

Nigel Hawthorne as the tormented priest gives a remarkably powerful portrait of suffering, also the more convincing for its restraint; Dai Bradley, as the child so tragically fought over, finds exactly the right note of wanton innocence; and D a v i d William as the Father Superior conveys his own two-edged pain with a fine resignation: he would make an admirable Inquisitor for the next "St. Joan."

The Fire That Consumes

Evening Standard, October 16, 1977Henry de Montherlant (1896-1972) was expelled from his school at the age of 16 on account of his friendship with a younger boy. The Abb� who brought about the expulsion had himself suspect motives for doing so.

When Montherlant dramatised the events nearly 40 years later his anguish was rekindled, and he would not allow productions of the play for some years. When at last he relented, the Comedie Francaise was entrusted with it and, by courtesy of Peter Daubeny, London was able to see "La ville dont le prince est un enfant" in 1971. The Fire tbat Consumes (Mermaid), Vivian Cox's admirably straight translation, is its first English production.

The boys, Adam Bareham and Dai Bradley, convey their bewildered innocence and indignation most convincingly. Their kiss in the Games Pavilion is the only blemish in Sir Bernard Miles's assured direction. They were not even "guilty" of this entirely natural act.

Nigel Hawthorne's playing of the Abb� is a revelation. He endows the man - played in the French production as a tight-lipped, cruel diciplinarian - with his innate warmth and humanity. Not that he glosses over the priest's duplicity - indeed, he takes him daringly to the edge of comedy - but he never forfeits our sympathy. The more cerebral French may quarrel with his interpretation but he moved me deeply.